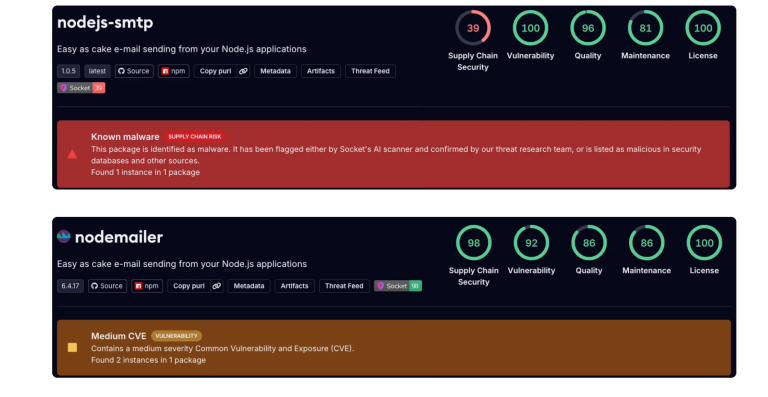

Low-profile droppers, long considered auxiliary tools in the arsenals of Android banking trojans and RATs, are undergoing a rapid and troubling transformation. According to ThreatFabric researchers, these once secondary instruments are now being actively deployed to deliver far simpler malware—ranging from spyware to SMS stealers. Most critically, their architecture has already been adapted to bypass Google’s new security framework known as the Pilot Program.

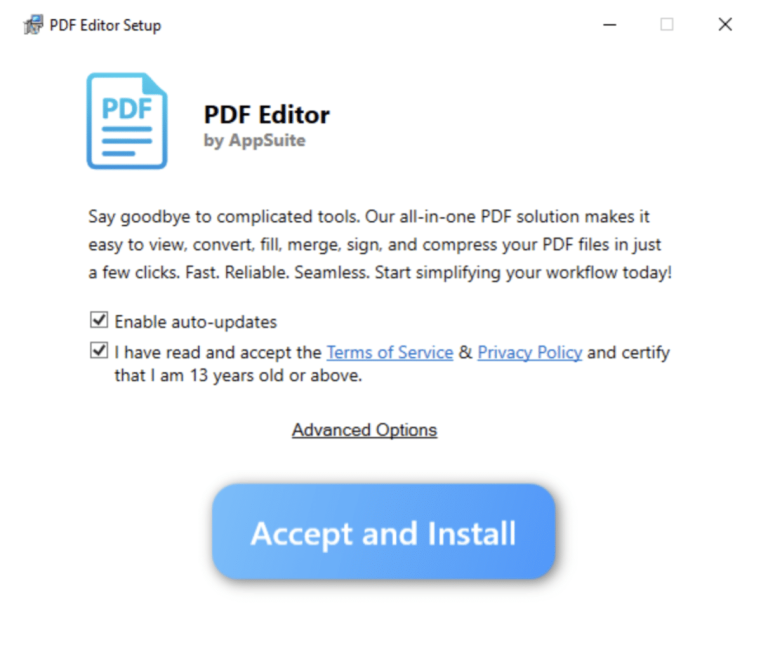

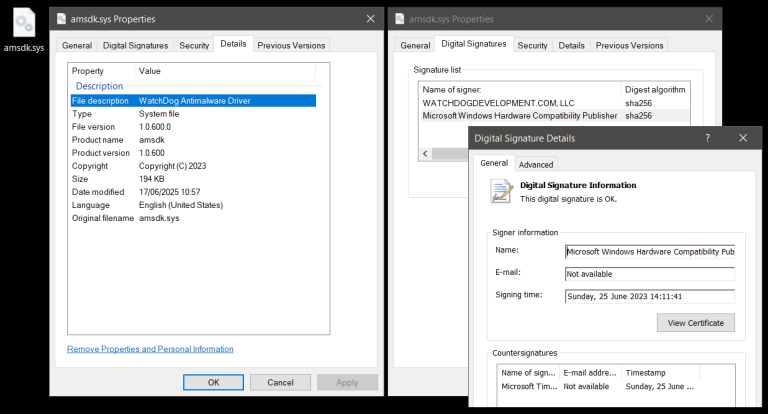

The essence of a dropper lies in its disguise: it appears to be an innocuous application, free of malicious indicators, yet once installed, it extracts and executes the real payload. This tactic enables it to evade initial security checks, including Play Protect. The approach has become especially relevant since Android 13 introduced stricter policies limiting access to APIs and sensitive permissions. Droppers, however, adapted swiftly—requesting elevated privileges such as Accessibility Services only after the payload is installed.

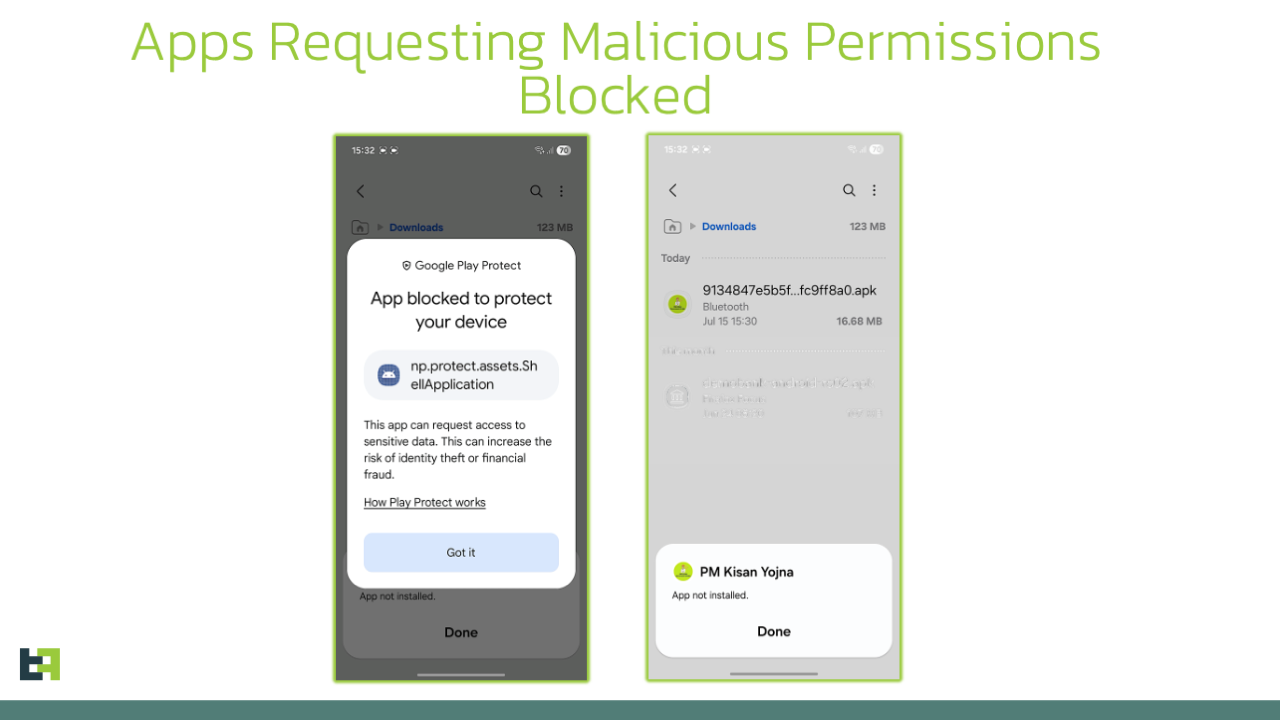

The Pilot Program was introduced by Google to combat financial fraud in high-risk regions, including India, Brazil, Thailand, and Singapore. Unlike the standard Play Protect scan, it scrutinizes applications during installation—particularly those loaded from third-party sources—and blocks them if suspicious permissions are detected, such as access to SMS, notifications, or accessibility functions. Yet attackers have already devised methods to circumvent these protections.

Modern droppers designed to evade the Pilot Program conduct the initial installation as silently as possible: no dangerous permission requests, no suspicious code, often masked by a simple “update” splash screen. In one experiment, researchers attempted to install a legitimate but permission-sensitive app, SMS Messenger, via a dropper. The dropper effortlessly bypassed the initial scan, presenting only an “Update” button. The true activity began later—once the user clicked, triggering the download or decryption of the malicious payload, along with the actual permission requests. In such cases, Play Protect may issue a warning, but the ultimate decision rests with the user.

This creates a time window between installation and activation of the malicious payload—precisely the gap exploited by attackers. Even simple malware that requires no special permissions now leverages droppers, since it significantly increases the likelihood of successful infiltration.

One striking example is RewardDropMiner, a multifunctional dropper that, at various stages, has been used to deliver spyware, activate backup malicious code, and even conduct covert Monero mining. In its latest version, RewardDropMiner.B, the mining and spyware features were removed—likely in response to exposure and identification of linked wallets.

RewardDropMiner, however, is only one representative of this new generation. Researchers have identified a growing family of droppers, including SecuriDropper, Zombinder, BrokewellDropper, HiddenCatDropper, and TiramisuDropper. Some employ two-phase installation via the Session Installer API, concealing real permission requests and masking malicious activity. Others, like Zombinder, spread aggressively through WhatsApp or counterfeit websites.

This strategy enables adversaries not merely to retain access to devices but to ensure payload delivery regardless of geography or Android defenses. In essence, droppers have evolved into universal installers of malware—capable of delivering threats of any scale, from trivial spyware to highly sophisticated banking trojans.

Experts stress that while Play Protect and the Pilot Program can thwart many threats, their effectiveness lasts only as long as defenses evolve in tandem. Attackers adapt swiftly—so swiftly that what is effective today may be obsolete tomorrow. The evolution of droppers illustrates this vividly: they are not disappearing but becoming sharper, stealthier, and more inventive, demanding an equally dynamic response from security solutions.