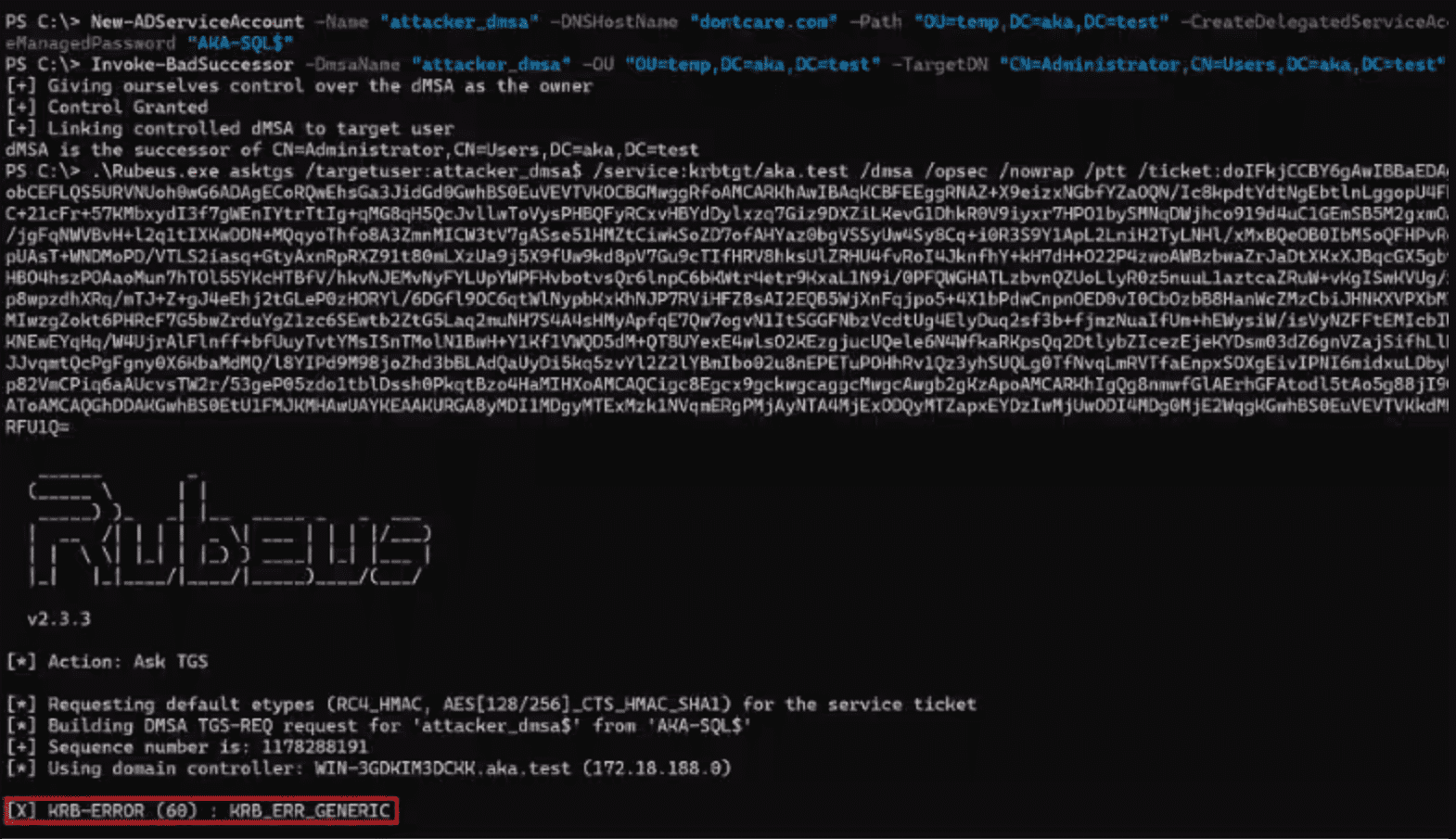

At DEF CON 2025, researchers from Akamai unveiled a study on a critical vulnerability in Windows Server 2025 known as BadSuccessor (CVE-2025-53779), which allows low-privileged users to instantly escalate their access to Domain Admin.

The flaw lay in the handling of a new type of account—delegated Managed Service Accounts (dMSA). The vulnerability enabled an attacker to bind a controlled dMSA to any account within Active Directory, including highly privileged and protected ones. Once this link was established, the Key Distribution Center (KDC) would treat the dMSA as the “successor” of the target account, inheriting its privileges in the PAC and issuing Kerberos keys accordingly.

What made this especially dangerous was the low barrier to exploitation: merely controlling any Organizational Unit (OU) in the domain was sufficient. An attacker could create a dMSA within such an OU and link it to a chosen account—without third-party tools or Group Policy modifications. The KDC fully accepted the configuration without validating the legitimacy of the link.

A few days after Akamai’s disclosure, Microsoft assigned the identifier CVE-2025-53779 and released a patch. The update did not block the linking attribute itself but modified the kdcsvc.dll component, requiring the KDC to verify reciprocity between the dMSA and the target account. Now, to obtain a Kerberos ticket, the dMSA and its “predecessor” must reference each other, mirroring the behavior of a genuine migration via migrateADServiceAccount. The one-sided binding that previously enabled instant privilege escalation no longer functions. However, as the researchers noted, this does not mean the method has been entirely neutralized.

Despite eliminating the direct escalation path, the BadSuccessor technique remains a concern because its underlying weakness—the lack of validation for the linking attribute—persists. This allows BadSuccessor to be repurposed in two new scenarios, both of interest to attackers and hazardous to defenders.

Scenario One: Credential and privilege hijacking (a stealthy alternative to “shadow” credentials). If an attacker already controls both a dMSA and a target account, linking them enables the attacker to obtain a Kerberos ticket for the dMSA and act on behalf of the victim through a separate entity. This tactic avoids suspicious activity tied directly to the compromised account and can evade monitoring systems. Moreover, Kerberos keys are extracted faster and with fewer resources than through Kerberoasting, since there is no need to register an SPN or attempt password cracking.

Scenario Two: A substitute for DCSync in compromised domains. Here, an attacker leverages a dMSA to obtain tickets containing keys for arbitrary accounts without issuing replication requests to a domain controller. This stealthier approach bypasses traditional DCSync detection signatures, reducing the likelihood of exposure.

To detect potential use of BadSuccessor post-patch, organizations are advised to enable auditing of dMSA attribute changes and monitor events tied to dMSA password retrieval or anomalous bindings between active users and dMSAs. Suspicious indicators include a previously disabled account suddenly linked to a new dMSA, or repeated password requests for a dMSA within a short timeframe.

Mitigation measures include deploying the CVE-2025-53779 patch across all Windows Server 2025 domain controllers and restricting access rights to OUs, containers, and dMSA objects. Only Tier 0 administrators should be permitted to manage dMSAs and their migration attributes.

Experts emphasize that BadSuccessor is not merely a flaw but an inherently vulnerable architectural technique—one that may remain relevant even after this particular exploit is closed. As with many Active Directory vulnerabilities, sealing one loophole does not guarantee that attackers will not discover another pathway built on the same mechanisms.