Most people remain unaware that their Wi-Fi and Bluetooth devices have quietly become part of a vast, global geolocation tracking system — open, precise, and alarmingly accessible. And if this sounds threatening, it is: any malicious actor can determine your location without ever leaving their couch.

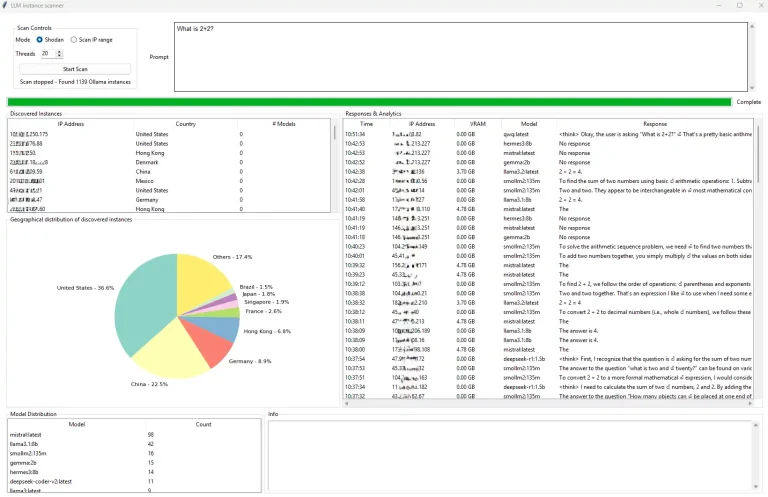

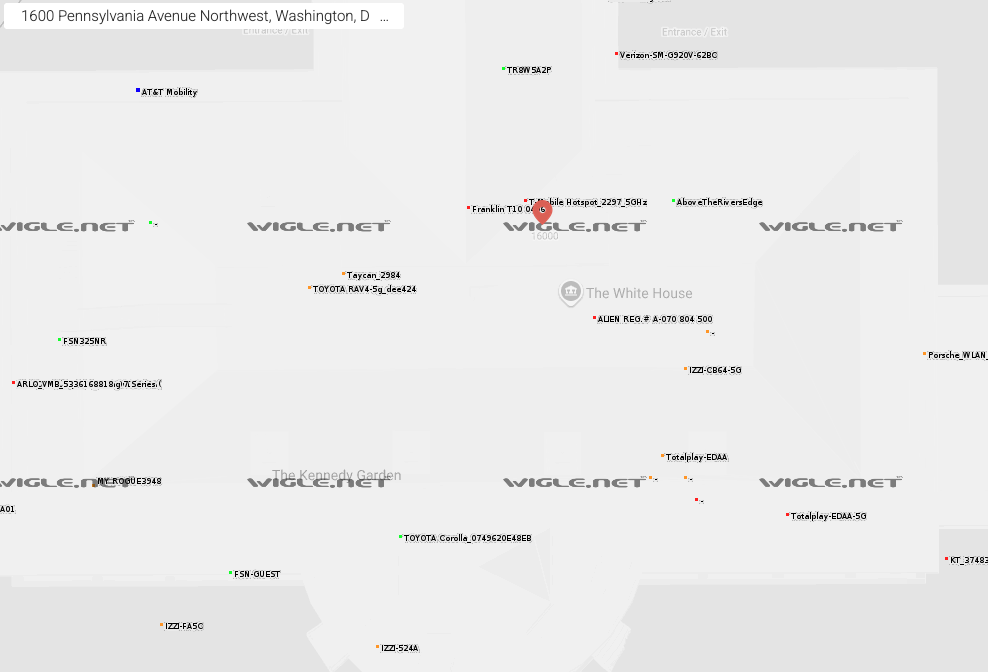

It begins with mapping services such as Wigle.net, along with the infrastructures of Apple, Google, Microsoft, and other giants, which collect massive datasets on wireless access points — both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. These records include not only SSIDs (network names), but also MAC addresses (BSSIDs), signal strength, encryption type, timestamps, and even estimated coordinates. Wigle publishes much of this information openly, meaning that with just a few clicks, anyone can view the networks surrounding Trump’s residence, the White House, or the Pentagon — complete with names such as Trump, Maul-tp-link, or myChevrolet 3012.

Historical data from such repositories reveal, for example, that at certain times the Pentagon made use of TP-Link and Huawei access points — hardly paragons of security. And it is not just routers at stake: smartphones, laptops, cars, headphones, and any device with a Wi-Fi or Bluetooth access point become glowing beacons in the surveillance landscape.

In practice, this means that anyone who knows a device’s MAC address can locate it. The rest is a matter of routine: connect to Google’s or Apple’s geolocation APIs, input two MAC addresses — say, a phone and a car — and retrieve their precise coordinates. Access to these APIs is often free or nearly so, requiring only a billing account; and in less scrupulous jurisdictions, unrestricted alternatives are available.

Today, the open database counts more than 1.67 billion Wi-Fi networks, 4.2 billion Bluetooth devices, and 27.5 million cell towers. With Wigle boasting fewer than a million contributors, the troves amassed by Apple, Google, and Microsoft are immeasurably larger.

Wi-Fi Positioning Systems (WPS) underpin a wide range of services — from Apple’s AirTag to mapping applications — functioning by comparing signal strengths against known router databases. Once your router has been “seen” by another device, its location is stored and repurposed to triangulate other gadgets, entirely without your knowledge.

In theory, users can “opt out.” Google, Apple, and Wigle advise appending _nomap to an SSID (e.g., HomeNetwork_nomap). Microsoft, however, now requires separate MAC registration on its site, having abandoned the older _optout suffix. To satisfy all vendors, your SSID might have to look something like MyWiFi_nomap_optout_notrack_offgrid. Even then, no law compels companies to honor such requests.

Wigle’s administrators emphasize that even if SSID beaconing is disabled, a network remains detectable through its traffic. Thus, hidden or unnamed networks can still enter the database. The same applies to Bluetooth — only worse: there is no opt-out equivalent, and MAC randomization is inconsistent or absent in many devices, especially headphones, fitness trackers, speakers, and similar consumer tech.

And even when MAC randomization is supported, advanced WPS systems and state agencies can often bypass it. In short, Bluetooth represents yet another hole in privacy, one without even the pretense of user consent.

What can be done? Experts recommend regularly changing SSIDs and MAC addresses — though this is impractical for most, particularly those renting ISP-provided equipment. Tech-savvy users may employ alternative firmware (such as hostap) to automate randomization. Encryption standards also matter: roughly 5% of networks still rely on insecure WEP or WPA1 protocols, which should never be used for anything critical.

For individuals concerned about surveillance, the best defense remains simple: disable Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and location services when not in use. More extreme advice includes storing your phone in a Faraday cage — unrealistic for daily life, yet effective. Vehicles are no less conspicuous: telemetry shows, for instance, a Chevrolet parked within range of the White House has “remained” there for quite some time, at least according to Wi-Fi signals.