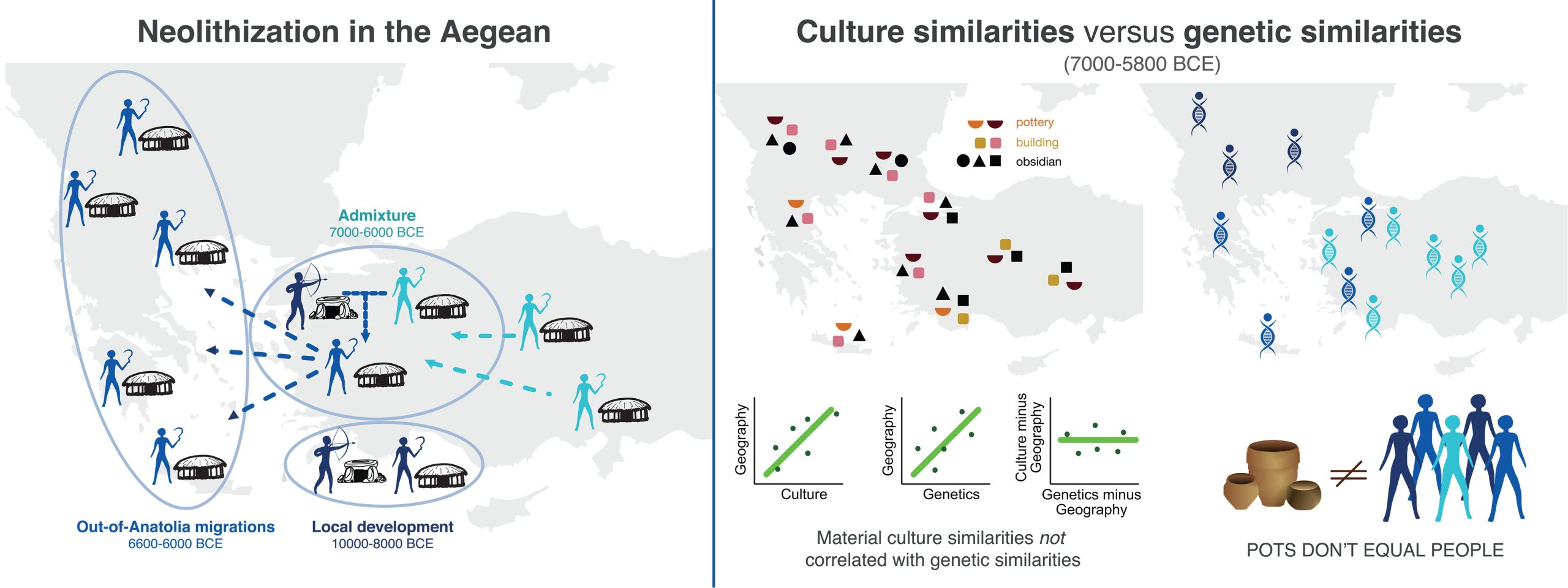

One of the most pivotal milestones in human history—the transition to a sedentary lifestyle and the advent of agriculture—has long been a subject of scholarly debate. The precise manner in which Neolithic culture spread from the Fertile Crescent through Anatolia to the Aegean region had, until recently, remained ambiguous. A new study by a Turkish-Swiss team of researchers now brings greater clarity, merging archaeological and genetic evidence.

Scientists from the Middle East Technical University and Hacettepe University in Ankara, along with colleagues from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, have demonstrated that cultural shifts occurred not solely through population movement but also via the exchange of ideas. In certain areas of Western Anatolia, the transition to an agrarian lifestyle began nearly ten thousand years ago, yet the genetic lineage of local populations remained largely unaltered—suggesting that agricultural practices may have proliferated without large-scale migration.

The foundation of this research is the analysis of DNA from an ancient inhabitant of Western Anatolia, approximately nine thousand years old—the oldest genetic material recovered from this region. Combined with dozens of other ancient samples and archaeological discoveries, the study revealed an extraordinary continuity in genetic makeup over a span of seven millennia. Meanwhile, material culture evolved significantly: people abandoned caves, constructed homes, adopted new tools, and integrated practices borrowed from neighboring communities.

To understand how innovations spread, the researchers compared genetic data with domestic artifacts uncovered at the same archaeological sites. This quantitative approach allowed them to directly correlate genomic shifts with cultural developments. They discovered that the appearance of new objects or technologies did not necessarily coincide with the arrival of foreign peoples. As the archaeologists aptly put it, “pottery does not equal people.”

Nevertheless, in certain regions—especially after 7000 BCE—genetic traces of migration became evident. In these instances, cultural transformation was accompanied by biological integration. In the Aegean region, later waves of migration introduced additional elements that would eventually shape the Neolithic cultures of Europe.

The authors emphasize that the Neolithic transition was not a singular, linear process, but rather a mosaic of events interweaving local innovation, mobility, and episodic population movements. This groundbreaking research was made possible through the efforts of scholars native to the very region under study. It serves as a testament to the importance of fostering research beyond traditional academic hubs and striving for a more equitable global scientific community. Modern analytical technologies now offer ever greater precision in tracing the dissemination of cultural innovation in antiquity.